This month’s article was ‘Does Guru Granth Sahib describe depression?’ by Kalra et al, published in the Indian Journal of Psychiatry in 2013. It can be found here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3705682/

The discussion began with a reflection that the article had a lot of information about Gurbani for those who are non-Sikh readers. The three writers are psychiatrists (as opposed to religious scholars). They were coming from a scientific perspective but had clearly done a large amount of cursory research on Gurbani, as indicated by the several tables which listed the names of God, and the number of times that the mind is mentioned. There was some basic discussion about Sikh beliefs in the introduction along with general history. However this was not comprehensive and it appeared that the authors had taken an Abrahamic approach to Sikhi which became prevalent after the Singh Sabha movement, as opposed to getting to grips with non-dualistic aspects of Sikh spirituality which would have provided a completely different perspective on depression.

It was made clear that the authors had translated the word Dukh to mean depression, and they hadn’t qualified their definition of depression. The members discussed whether this translation of ‘Dukh’ was fair or accurate. It was felt that Dukh refers to any state of detachment from the Guru, and is our mindset or perception of things, and does not necessarily refer to physical pain or any particular definition of mental illness. It became apparent as the article went on that they were referring to milder forms of psychological depression as opposed to biochemical depression in which there is a deficiency of serotonin in the brain requiring ongoing replacement. At one point the word psychosis was used in the article, again without qualification of what this meant, and in the context of their discussion seems far-reached from the clinically accepted definition of psychosis.

There was discussion amongst the members about the causes of depression and the fact that depression is often a physical illness (and changes in the biochemistry of the brain have been proven). Recently there has been great interest in the use of faith and spirituality in dealing with depression. However there isn’t the same level of interest in using faith and spirituality to heal other physical ailments such as broken limbs, and for good reason. Therefore we need to be careful when talking about such subjects so that we are clear that spirituality can provide solutions and tools to manage to milder forms of illness (including some types of depression and pain) but should not be promoted as being the only tools available for all types of depression.

It was clear that the authors’ agenda was to prove that Guru Granth Sahib Ji does mention depression, but their arguments were devalued by their approach. The members wondered whether it would have better for the authors to discuss the existence of depression and then use Gurbani to explore what tools it provides for depression management, rather than attempting to project or fit illnesses within the angs Guru Granth Sahib Ji. There is no doubt that faith can be a great healer, and the members discussed that many faiths attempt to remove troubles of the self and instead place these troubles in the hands of God, which can be powerful in some cases. The article specifically mentioned this as being an aspect of Sikhi. Similarly spiritual arts including music have been proven to be helpful in many illnesses including mental illnesses.

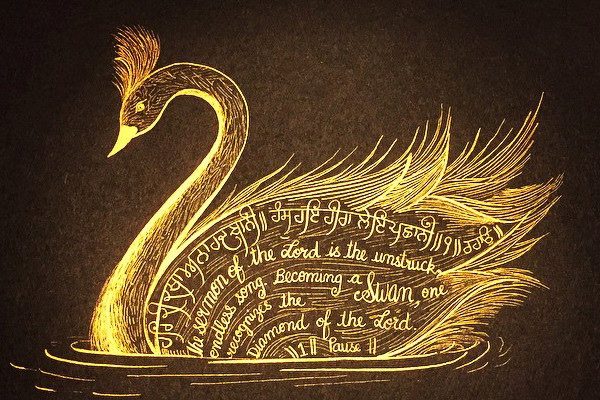

The authors raised the question of whether Sikh communities avoided access to medical help for mental illness, but only discussed this very briefly with reference to the influence of karma on people’s perceptions of whether they are deserving of illness. Members debated the influence of karams on illness and whether this is relevant when treating people for illness. Members felt that the authors had taken many words from Gurbani out of context, despite the importance of examining context and the broader message behind the Guru’s words.For example, anyone with any understanding of Gurbani knows the world isn’t divided into Manmukhs and Gurmukhs but instead that we all contain aspects of light and dark which we constantly struggle with. Better metaphors could have been chosen to describe the emotions associated with depression e.g. the mind drowning and the wisdom of the Guru pulling the individual up from the blackness of the ocean.

This led onto a discussion about the practical approaches that Gurbani recommends for maintaining emotional health. Even in scientific circles, integrative approaches such as mindfulness (alongside medicine) have been increasingly used to manage mental illness. Gurbani similarly recommends meditation as a way of healing the mind, but in such a way that minimises one’s ego. The members discussed how this can be used in clinical practice and reference was made to a clinical psychologist Kala Singh in Canada who utilises some aspects of Gurmat to help tailor cognitive strategies for Sikhs suffering with mental health problems (see Spirituality and Health International, DOI 10.1002/shi.331).

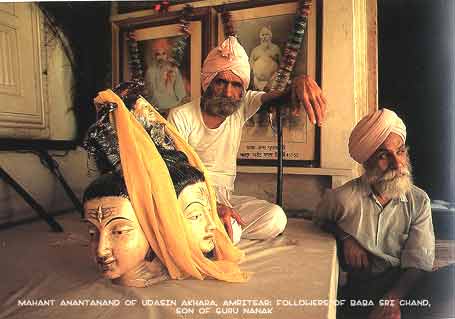

The members discussed the ICD-10 criteria for depression and how this is not absolute (and essentially is consensus opinion). The criteria for depression also depends on one’s cultural background i.e. what is considered mental illness in one culture may not be considered mental illness in another culture. An interesting point was raised regarding the fact that, by today’s standards, it could be considered that Guru Nanak Dev Ji was depressed. This is because he went through a period of time in his life where he withdrew from his family and appeared to have anhedonia, poor appetite and could be considered by outsiders to have low mood. A physical physician came to see treat him but was unable to do so. We know, of course, that Guru Nanak Dev Ji was not depressed as such, but was spiritually elevated and focused on a relationship with the Divine. This raises interesting questions about the line between devotion and how its effect can be perceived by others. It is also made much more complex by the fact that many people with true mental illness perceive that they are communicating with Jesus or God and it can be difficult to tell whether this is illness or true religion.

Overall, this topic is an important one to address, but the members of the book club felt that this article did not do it justice. Rather than addressing depression, it addressed general emotional distress. Despite this some valid points were made regarding the importance of understanding the mind, building a relationship with the Guru and meditation.