This month’s book was ‘The Golden Temple: Its Theo-political Status’ by Sirdar Kapur Singh. A copy of the book can be found here.

Summary of key points discussed:

- Ancient history of Amritsar’s sarovar and its relevance to Sikhi

- Attitude of Sikhs in denying their association with previous cultures and religions

- Background of the author Sardar Kapur Singh

- Discussion on the doctrine of double sovereignty

- A Sikh is first bound by truth and morality above allegiance to any country

- The Panth should be treated a collective group rather than a collection of individuals when making political and national decisions

- What are the implications for Sikhs today in view of the above?

- Examples of Sikhs in power from past times and comparisons made with the above principles

- Discussion of the misuse of power and structures within our Panth and recognition that these are not in keeping with the Sikh tradition

Full Discussion

The discussion began with many members reflecting on the new knowledge they had gained from reading this relatively short, but very well-researched and well-written book by Kapur Singh. Particularly illuminating were the historical aspects of Harmandar Sahib’s sarovar including references to its importance in Tibetan Buddhist history, the ancient Indus Civilisation and more recent cultures and the importance of sacred lakes in many different religions. These relatively unknown aspects of the Sarovar highlighted that there is a lot more history surrounding the Golden Temple than many Sikhs believe today. We have become detached from our own significance, forgetting our own place in history. The concept and design of Harmandar Sahib highlights universal principles, ‘the proposed centre of a world-culture and world-religion’. This acted to level out the diverging forces of Hindus and Muslims within India. An example of this was the Sai Mian Mir setting the foundation stone.

It could be argued that the ancient history surrounding the site of Harmandar Sahib does not feel relevant to today, but it provides balance and perspective to Sikhi as we see it today. Why did Guru Ramdas Sahib choose this particular site? The Sakhi of the yogi of Santokhsar waiting for the touch of the Guru for many centuries was particularly inspiring, especially as there is a Gurdwara commemorating this event near Harmandar Sahib. However there is a lack of common knowledge regarding this event and even at the Gurdwara Sahib there isn’t much information on the history. This may be reflective of our own Panth’s lack of awareness but also external forces who don’t want to give credence to the depth of our own theological and political history. Many Sikhs don’t like associating themselves with ‘pre-Sikh’ history but these stories are the reality of our history. Conversely it is interesting to note that other faiths such as Buddhism do not shy away from claiming an association with Harmandar Sahib e.g. in view of the fact that some of their historical figures are thought to be born there.

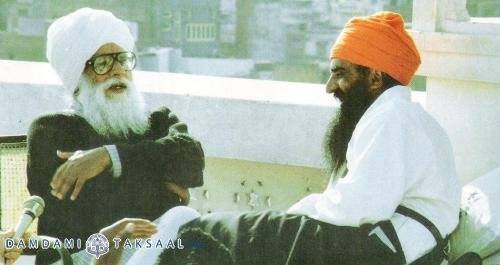

The members briefly discussed the background of Sardar Kapur Singh, including his instrumental part in writing the Anandpur Resolution (although he did not formally put his name to this document). It was recognised that this book did not contain as many references as would be expected. This may be because the full book has been truncated on the internet, rather than due to a paucity of references. Sardar Kapur Singh was one of the most highly recognised Sikh writers in the 1900s and was the first person to be awarded the title of National Professor of Sikhism.

One of the key concepts highlighted in this book was the doctrine of double sovereignty. This concept highlights that the state does not have the right to total power over its citizens due to the requirement of Sikhs to pay allegiance to truth and morality above all else. In this way the ideal state is observed to be pluralistic. The first obligation of a Sikh is not to be a slave but to obey the laws of righteousness. In this way, despite the Sikhs being a minority in the past (and despite the fact that they will be in years to come), this is a powerful tool for influencing bigger numbers of people.

Sardar Kapur Singh made reference to the importance of Sikhs being addressed as a group when making decisions. There were similarities to other distant empires of the past (e.g. Ottoman empires) which had societies where different sections of the community were treated as distinct groups. This is an unusual concept nowadays and is at odds with the societies we tend to live in. The importance of Panth (rather than single voices) was emphasised by the author. E.g. Maharaja Ranjit Singh himself had to bow to the supremacy of Akaal Takht, bowing to the above concept. Sardar Kapur Singh recognises that Sikhs are essentially a threat to all states due to their reliance on truth and morality as a benchmark. This clearly relies on the Sikhs of today understanding what the truth of the Guru actually means.

The point was raised that sovereign nations would never allow one group to retain distinct traditions if this contravened the law. However the chances of the Sikhs ever coming into conflict with a nation’s laws would be unlikely, unless a nation’s laws were resulting in the oppression of its citizens. Many members felt that politics and religion were intrinsically linked together and that one couldn’t go in hand without the other. Other members felt that they should be kept separate. There was a discussion regarding whether religions all feel that their individual religious beliefs are right and all others are wrong. The goal of a Sikhi is to ensure that anyone, regardless of their religion, is nurtured to be the best possible person they can be. Whether that means they are the best Hindu, best Muslim or best Christian etc. The goals of many religions of the world are to attain heaven, but a Sikh’s goal is a higher truth. So although many people think all religions have the same purpose and that we are all climbing different paths on the same mountain, this is not strictly true.

Sardar Kapur Singh didn’t make reference to Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s time of power (which many regard today as being the pinnacle of Sikh/Punjab’s glory in modern history). However he did make reference to Banda Singh Bahadur’s reign and used the experiences and decisions of Banda Singh Bahadur as an example of the Sikh doctrine of double sovereignty.

The members reflected that current Panthic organisation and structure mimics the structure of the Indian government. For example, each individual has a vote and there is a structure of committees and political parties which govern our Gurdwaras. This is not traditionally the way that our Gurdwaras were intended to be governed. But part of this influence stems from the British colonisation of India and the adoption of British customs which have been integrated into our political system.

The discussion concluded with the recognition of the significance of the last passage in the book, where Sardar Kapur Singh states that “a satisfied and properly integrated-to-the-nation Sikh people can be an invaluable and lasting asset to any state… just as a frustrated or suppressed Sikh people can an obvious weakness in the strength of the nation.”

This month the book club discussed the book named ‘The Sikh Army’ by Ian Heath and Michael Perry. The book can be found

This month the book club discussed the book named ‘The Sikh Army’ by Ian Heath and Michael Perry. The book can be found